Brugada Syndrome Workup: Approach Considerations, Electrocardiography, Electrophysiologic Study

Many patients with Brugada syndrome are young and otherwise healthy and may present with syncope. Patients with syncope should not be assumed to have a benign condition, and a 12-lead ECG should be performed.

A drug challenge with a sodium channel blocker should be considered in patients with syncope in whom no obvious cause is found. An experienced physician should interpret the ECGs, and an electrophysiologist should review them if possible.

Further testing may be indicated to exclude other diagnostic possibilities.

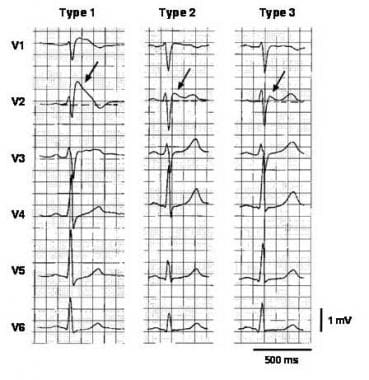

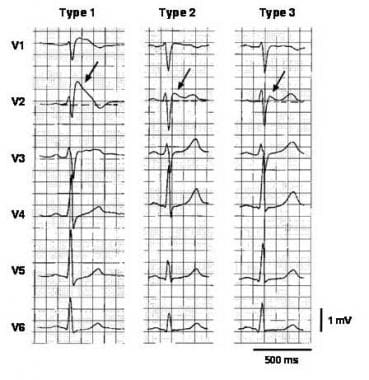

Three ECG patterns have been described in Brugada syndrome(see the image and table below). Placing the right precordial leads in the second intercostal space has been proposed to add sensitivity to the ECG diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.Exercise stress testing may suppress ECG changes and arrhythmias.

Three types of ST-segment elevation in Brugada syndrome, as shown in the precordial leads on ECG in the same patient at different times. Left panel shows a type 1 ECG pattern with pronounced elevation of the J point (arrow), a coved-type ST segment, and an inverted T wave in V1 and V2. The middle panel illustrates a type 2 pattern with a saddleback ST-segment elevated by >1 mm. The right panel shows a type 3 pattern in which the ST segment is elevated < 1 mm. According to a consensus report (Antzelevitch, 2005), the type 1 ECG pattern is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Modified from Wilde, 2002. Image courtesy of Richard Nunez, MD, and EMedHome.com (http://www.emedhome.com/).

Three types of ST-segment elevation in Brugada syndrome, as shown in the precordial leads on ECG in the same patient at different times. Left panel shows a type 1 ECG pattern with pronounced elevation of the J point (arrow), a coved-type ST segment, and an inverted T wave in V1 and V2. The middle panel illustrates a type 2 pattern with a saddleback ST-segment elevated by >1 mm. The right panel shows a type 3 pattern in which the ST segment is elevated < 1 mm. According to a consensus report (Antzelevitch, 2005), the type 1 ECG pattern is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Modified from Wilde, 2002. Image courtesy of Richard Nunez, MD, and EMedHome.com (http://www.emedhome.com/).

Table. ECG Patterns in Brugada Syndrome (Open Table in a new window)

Recently, the QRS duration on 12-lead ECG has been suggested as a risk marker for vulnerability to dangerous arrhythmias.Inferolateral repolarization abnormalities have also been proposed to be a marker of risk.

Asymptomatic patients with a type 1 ECG pattern on routine ECG represent a difficult case. According to the latest consensus guidelines, a clinical electrophysiologist should evaluate patients in this situation.Patients should be risk-stratified using the techniques described below, and a decision on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation should be made accordingly.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) and Brugada syndrome may be difficult to differentiate in some cases. Late potentials on signal-averaged ECG may reveal the fibrofatty degeneration of the right ventricle seen in ARVC.

In some patients, the intravenous administration of drugs that block sodium channels may unmask or modify the ECG pattern, aiding in diagnosis and/or risk stratification in some individuals. Infuse flecainide 2 mg/kg (maximum 150 mg) over 10 minutes, procainamide 10 mg/kg over 10 minutes, ajmaline 1 mg/kg over 5 minutes, or pilsicainide 1 mg/kg over 10 minutes. This challenge should be performed with continuous cardiac monitoring and in a setting equipped for resuscitation.

In patients with a normal baseline ECG, the results are positive when the drug generates a J wave with an absolute amplitude of 2 mm or more in leads V1, V2, and/or V3 with or without an RBBB. Administration of the drug should be stopped when the result is positive, when ventricular arrhythmia occurs, or when QRS widening of greater than 30% is observed.

Isoproterenol and sodium lactate may be effective as antidotes if the sodium channel blocker induces an arrhythmia, and the isoproterenol response may also have diagnostic use.

This drug test should not be performed in patients with a type 1 ECG pattern (see Table above) because it adds no new information.

In patients with the type 2 or 3 patterns, the drug challenge is recommended to clarify the diagnosis.The sensitivity and specificity of drug challenge testing is not yet confirmed. A 2012 study examining patients with type 2 or 3 patterns showed that a positive drug challenge in symptomatic patients was associated with adverse events. However, asymptomatic patients with a similar result had a low event rate. This study suggests that a drug challenge may aid in risk stratification for symptomatic patients with a nondiagnostic ECG, but may not be justified in asymptomatic patients.

Some investigators use an electrophysiologic study (EPS) to determine the inducibility of arrhythmias, in an effort to risk-stratify patients with Brugada syndrome. However, the predictive value of this approach is debated. In 2001, Brugada showed that inducibility may be a good predictor of outcome.However, in 2002, Priori reported a poor predictive value of invasive testing.A subsequent study by Gehi concluded that EPS was not of use in guiding the management of patients with Brugada syndrome.

More recently, investigators independently examining a large series of patients from Europe and Japan have failed to find any predictive value for EPS. In the large registry of Brugada syndrome patients from Europe, only symptoms and a spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern, but not EPS, were predictive of arrhythmic events.. In the smaller Japanese registry, only family history of sudden cardiac death at younger than 45 years and inferolateral early repolarization pattern on ECG predicted cardiac events.

A study by Priori et al enrolled 308 patients with no history of cardiac arrest and a spontaneous or drug-induced type I ECG pattern.Seventy eight of the patients had an ICD implanted prophylactically. EPS with a consistent stimulation protocol was performed on all patients; at a mean follow-up of 34 months, no differences were found in the incidence of appropriate ICD shocks or cardiac arrest between patients who were inducible and patients who were noninducible. Significant predictors of arrhythmia in this study included syncope and a spontaneous type I ECG pattern, a ventricular effective refractory period of less than 200 ms on EPS, and a fragmented QRS in the anterior precordial ECG leads.

Investigators from the United Kingdom examined a group of probands who suffered sudden arrhythmic death believed to be due to Brugada syndrome.A retrospective review of risk factors determined that these patients would not have been considered high risk, calling into question the sensitivity of current risk factors (eg, symptoms, type I ECG pattern). However, few ECGs were available for examination in the probands with sudden death .

Check serum potassium and calcium levels in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads.

Both hypercalcemia and hyperkalemia may generate an ECG pattern similar to that of Brugada syndrome.

Laboratory markers, such as creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) and troponin, should be checked in patients who have symptoms compatible with an acute coronary syndrome. Elevations indicate cardiac injury.

Patients with high likelihood of Brugada syndrome may be genetically tested for a mutation in SCN5A, which codes for the alpha subunit Nav 1.5 of the cardiac sodium channel. The results of this test support the clinical diagnosis and are important for the early identification of family members at potential risk. However, the yield of genetic testing remains relatively low at this time, with mutations in SCN5A found in only 11-28% of index cases.

Echocardiography and/or MRI should be performed, mainly to exclude arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. However, these studies are also used to assess for other potential causes of arrhythmias, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, unsuspected myocardial injury, myocarditis, or aberrant coronary origins.

Treatment & Management

Jose M Dizon, MD Associate Professor of Medicine and Surgery, Clinical Electrophysiology Laboratory, Division of Cardiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; Consulting Staff, Department of Medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Columbia University Medical Center

Jose M Dizon, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society

Coauthor(s)

Tamim M Nazif, MD Fellow, Division of Cardiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Tamim M Nazif, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Ronald J Oudiz, MD, FACP, FACC, FCCP Professor of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine; Director, Liu Center for Pulmonary Hypertension, Division of Cardiology, LA Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Ronald J Oudiz, MD, FACP, FACC, FCCP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, American College of Physicians, American Heart Association

Disclosure: Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Lung Biotechnology, United Therapeutics<br/>Received research grant from: Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Ikaria, Lung Biotechnology, Pfizer, Reata, United Therapeutics<br/>Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Lung Biotechnology, Medtronic, Reata, United Therapeutics.

Chief Editor

Jeffrey N Rottman, MD Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; Chief, Department of Cardiology, Nashville Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Jeffrey N Rottman, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Heart Association, Heart Rhythm Society

Justin D Pearlman, MD, ME, PhD, FACC, MA Chief, Division of Cardiology, Director of Cardiology Consultative Service, Director of Cardiology Clinic Service, Director of Cardiology Non-Invasive Laboratory, Chair of Institutional Review Board, University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine

Justin D Pearlman, MD, ME, PhD, FACC, MA is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, American College of Physicians, American Federation for Medical Research, Radiological Society of North America

References

Schematics show the 3 types of action potentials in the right ventricle: endocardial (End), mid myocardial (M), and epicardial (Epi). A, Normal situation on V2 ECG generated by transmural voltage gradients during the depolarization and repolarization phases of the action potential. B-E, Different alterations of the epicardial action potential that produce the ECG changes observed in patients with Brugada syndrome. Adapted from Antzelevitch, 2005.

Three types of ST-segment elevation in Brugada syndrome, as shown in the precordial leads on ECG in the same patient at different times. Left panel shows a type 1 ECG pattern with pronounced elevation of the J point (arrow), a coved-type ST segment, and an inverted T wave in V1 and V2. The middle panel illustrates a type 2 pattern with a saddleback ST-segment elevated by >1 mm. The right panel shows a type 3 pattern in which the ST segment is elevated < 1 mm. According to a consensus report (Antzelevitch, 2005), the type 1 ECG pattern is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Modified from Wilde, 2002. Image courtesy of Richard Nunez, MD, and EMedHome.com (http://www.emedhome.com/).

Table. ECG Patterns in Brugada Syndrome

Approach Considerations

Many patients with Brugada syndrome are young and otherwise healthy and may present with syncope. Patients with syncope should not be assumed to have a benign condition, and a 12-lead ECG should be performed.

A drug challenge with a sodium channel blocker should be considered in patients with syncope in whom no obvious cause is found. An experienced physician should interpret the ECGs, and an electrophysiologist should review them if possible.

Further testing may be indicated to exclude other diagnostic possibilities.

Electrocardiography

Three ECG patterns have been described in Brugada syndrome(see the image and table below). Placing the right precordial leads in the second intercostal space has been proposed to add sensitivity to the ECG diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.Exercise stress testing may suppress ECG changes and arrhythmias.

Three types of ST-segment elevation in Brugada syndrome, as shown in the precordial leads on ECG in the same patient at different times. Left panel shows a type 1 ECG pattern with pronounced elevation of the J point (arrow), a coved-type ST segment, and an inverted T wave in V1 and V2. The middle panel illustrates a type 2 pattern with a saddleback ST-segment elevated by >1 mm. The right panel shows a type 3 pattern in which the ST segment is elevated < 1 mm. According to a consensus report (Antzelevitch, 2005), the type 1 ECG pattern is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Modified from Wilde, 2002. Image courtesy of Richard Nunez, MD, and EMedHome.com (http://www.emedhome.com/).

Three types of ST-segment elevation in Brugada syndrome, as shown in the precordial leads on ECG in the same patient at different times. Left panel shows a type 1 ECG pattern with pronounced elevation of the J point (arrow), a coved-type ST segment, and an inverted T wave in V1 and V2. The middle panel illustrates a type 2 pattern with a saddleback ST-segment elevated by >1 mm. The right panel shows a type 3 pattern in which the ST segment is elevated < 1 mm. According to a consensus report (Antzelevitch, 2005), the type 1 ECG pattern is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Modified from Wilde, 2002. Image courtesy of Richard Nunez, MD, and EMedHome.com (http://www.emedhome.com/).Table. ECG Patterns in Brugada Syndrome (Open Table in a new window)

| Characteristic | Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 |

| J wave amplitude | ≥2 mm | ≥2 mm | ≥2 mm |

| T wave | Negative | Positive or biphasic | Positive |

| ST-T configuration | Cover-type | Saddleback | Saddleback |

| ST segment, terminal portion | Gradually descending | Elevated by ≥1 mm | Elevated by < 1 mm |

Recently, the QRS duration on 12-lead ECG has been suggested as a risk marker for vulnerability to dangerous arrhythmias.Inferolateral repolarization abnormalities have also been proposed to be a marker of risk.

Asymptomatic patients with a type 1 ECG pattern on routine ECG represent a difficult case. According to the latest consensus guidelines, a clinical electrophysiologist should evaluate patients in this situation.Patients should be risk-stratified using the techniques described below, and a decision on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation should be made accordingly.

Signal-averaged ECG

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) and Brugada syndrome may be difficult to differentiate in some cases. Late potentials on signal-averaged ECG may reveal the fibrofatty degeneration of the right ventricle seen in ARVC.

Challenge with sodium channel blockers

In some patients, the intravenous administration of drugs that block sodium channels may unmask or modify the ECG pattern, aiding in diagnosis and/or risk stratification in some individuals. Infuse flecainide 2 mg/kg (maximum 150 mg) over 10 minutes, procainamide 10 mg/kg over 10 minutes, ajmaline 1 mg/kg over 5 minutes, or pilsicainide 1 mg/kg over 10 minutes. This challenge should be performed with continuous cardiac monitoring and in a setting equipped for resuscitation.

In patients with a normal baseline ECG, the results are positive when the drug generates a J wave with an absolute amplitude of 2 mm or more in leads V1, V2, and/or V3 with or without an RBBB. Administration of the drug should be stopped when the result is positive, when ventricular arrhythmia occurs, or when QRS widening of greater than 30% is observed.

Isoproterenol and sodium lactate may be effective as antidotes if the sodium channel blocker induces an arrhythmia, and the isoproterenol response may also have diagnostic use.

This drug test should not be performed in patients with a type 1 ECG pattern (see Table above) because it adds no new information.

In patients with the type 2 or 3 patterns, the drug challenge is recommended to clarify the diagnosis.The sensitivity and specificity of drug challenge testing is not yet confirmed. A 2012 study examining patients with type 2 or 3 patterns showed that a positive drug challenge in symptomatic patients was associated with adverse events. However, asymptomatic patients with a similar result had a low event rate. This study suggests that a drug challenge may aid in risk stratification for symptomatic patients with a nondiagnostic ECG, but may not be justified in asymptomatic patients.

Electrophysiologic Study

Some investigators use an electrophysiologic study (EPS) to determine the inducibility of arrhythmias, in an effort to risk-stratify patients with Brugada syndrome. However, the predictive value of this approach is debated. In 2001, Brugada showed that inducibility may be a good predictor of outcome.However, in 2002, Priori reported a poor predictive value of invasive testing.A subsequent study by Gehi concluded that EPS was not of use in guiding the management of patients with Brugada syndrome.

More recently, investigators independently examining a large series of patients from Europe and Japan have failed to find any predictive value for EPS. In the large registry of Brugada syndrome patients from Europe, only symptoms and a spontaneous type 1 Brugada ECG pattern, but not EPS, were predictive of arrhythmic events.. In the smaller Japanese registry, only family history of sudden cardiac death at younger than 45 years and inferolateral early repolarization pattern on ECG predicted cardiac events.

A study by Priori et al enrolled 308 patients with no history of cardiac arrest and a spontaneous or drug-induced type I ECG pattern.Seventy eight of the patients had an ICD implanted prophylactically. EPS with a consistent stimulation protocol was performed on all patients; at a mean follow-up of 34 months, no differences were found in the incidence of appropriate ICD shocks or cardiac arrest between patients who were inducible and patients who were noninducible. Significant predictors of arrhythmia in this study included syncope and a spontaneous type I ECG pattern, a ventricular effective refractory period of less than 200 ms on EPS, and a fragmented QRS in the anterior precordial ECG leads.

Investigators from the United Kingdom examined a group of probands who suffered sudden arrhythmic death believed to be due to Brugada syndrome.A retrospective review of risk factors determined that these patients would not have been considered high risk, calling into question the sensitivity of current risk factors (eg, symptoms, type I ECG pattern). However, few ECGs were available for examination in the probands with sudden death .

Potassium and Calcium Levels

Check serum potassium and calcium levels in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads.

Both hypercalcemia and hyperkalemia may generate an ECG pattern similar to that of Brugada syndrome.

Creatine Kinase-MB and Troponin

Laboratory markers, such as creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) and troponin, should be checked in patients who have symptoms compatible with an acute coronary syndrome. Elevations indicate cardiac injury.

Genetic Testing

Patients with high likelihood of Brugada syndrome may be genetically tested for a mutation in SCN5A, which codes for the alpha subunit Nav 1.5 of the cardiac sodium channel. The results of this test support the clinical diagnosis and are important for the early identification of family members at potential risk. However, the yield of genetic testing remains relatively low at this time, with mutations in SCN5A found in only 11-28% of index cases.

Echocardiography and/or MRI

Echocardiography and/or MRI should be performed, mainly to exclude arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. However, these studies are also used to assess for other potential causes of arrhythmias, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, unsuspected myocardial injury, myocarditis, or aberrant coronary origins.

Treatment & Management

Jose M Dizon, MD Associate Professor of Medicine and Surgery, Clinical Electrophysiology Laboratory, Division of Cardiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; Consulting Staff, Department of Medicine, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Columbia University Medical Center

Jose M Dizon, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society

Coauthor(s)

Tamim M Nazif, MD Fellow, Division of Cardiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Tamim M Nazif, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Ronald J Oudiz, MD, FACP, FACC, FCCP Professor of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine; Director, Liu Center for Pulmonary Hypertension, Division of Cardiology, LA Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Ronald J Oudiz, MD, FACP, FACC, FCCP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, American College of Physicians, American Heart Association

Disclosure: Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Lung Biotechnology, United Therapeutics<br/>Received research grant from: Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Ikaria, Lung Biotechnology, Pfizer, Reata, United Therapeutics<br/>Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Lung Biotechnology, Medtronic, Reata, United Therapeutics.

Chief Editor

Jeffrey N Rottman, MD Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; Chief, Department of Cardiology, Nashville Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Jeffrey N Rottman, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Heart Association, Heart Rhythm Society

Justin D Pearlman, MD, ME, PhD, FACC, MA Chief, Division of Cardiology, Director of Cardiology Consultative Service, Director of Cardiology Clinic Service, Director of Cardiology Non-Invasive Laboratory, Chair of Institutional Review Board, University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine

Justin D Pearlman, MD, ME, PhD, FACC, MA is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Cardiology, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, American College of Physicians, American Federation for Medical Research, Radiological Society of North America

References

- Bordachar P, Reuter S, Garrigue S, Caï X, Hocini M, Jaïs P, et al. Incidence, clinical implications and prognosis of atrial arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2004 May. 25(10):879-84. [Medline].

- Take Y, Morita H, Toh N, Nishii N, Nagase S, Nakamura K, et al. Identification of high-risk syncope related to ventricular fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2012 May. 9(5):752-9. [Medline].

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J, Brugada R, Nademanee K, Towbin J. The Brugada syndrome. Clinical approaches to tachyarrhythmias. Armonk NY: Futura Publishing Company; 1999.

- Frustaci A, Priori SG, Pieroni M, Chimenti C, Napolitano C, Rivolta I, et al. Cardiac histological substrate in patients with clinical phenotype of Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005 Dec 13. 112(24):3680-7. [Medline].

- Martini B, Nava A, Thiene G, Buja GF, Canciani B, Scognamiglio R, et al. Ventricular fibrillation without apparent heart disease: description of six cases. Am Heart J. 1989 Dec. 118(6):1203-9. [Medline].

- Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Determinants of sudden cardiac death in individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of Brugada syndrome and no previous cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003 Dec 23. 108(25):3092-6. [Medline].

- Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992 Nov 15. 20(6):1391-6. [Medline].

- Vorobiof G, Kroening D, Hall B, Brugada R, Huang D. Brugada syndrome with marked conduction disease: dual implications of a SCN5A mutation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008 May. 31(5):630-4. [Medline].

- Kusano KF, Taniyama M, Nakamura K, Miura D, Banba K, Nagase S, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome relationships of gene mutation, electrophysiology, and clinical backgrounds. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Mar 25. 51(12):1169-75. [Medline].

- Alings M, Wilde A. "Brugada" syndrome: clinical data and suggested pathophysiological mechanism. Circulation. 1999 Feb 9. 99(5):666-73. [Medline].

- Meregalli PG, Wilde AA, Tan HL. Pathophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome: depolarization disorder, repolarization disorder, or more?. Cardiovasc Res. 2005 Aug 15. 67(3):367-78. [Medline].

- Nagase S, Kusano KF, Morita H, Nishii N, Banba K, Watanabe A, et al. Longer repolarization in the epicardium at the right ventricular outflow tract causes type 1 electrocardiogram in patients with Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Mar 25. 51(12):1154-61. [Medline].

- Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J, Brugada R. Brugada syndrome: from cell to bedside. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2005 Jan. 30(1):9-54. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Postema PG, van Dessel PF, Kors JA, Linnenbank AC, van Herpen G, Ritsema van Eck HJ, et al. Local depolarization abnormalities are the dominant pathophysiologic mechanism for type 1 electrocardiogram in brugada syndrome a study of electrocardiograms, vectorcardiograms, and body surface potential maps during ajmaline provocation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Feb 23. 55(8):789-97. [Medline].

- Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Alders M, Benito B, Berthet M, Brugada J, et al. An international compendium of mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel in patients referred for Brugada syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2010 Jan. 7(1):33-46. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Antzelevitch C, Pollevick GD, Cordeiro JM, Casis O, Sanguinetti MC, Aizawa Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cardiac calcium channel underlie a new clinical entity characterized by ST-segment elevation, short QT intervals, and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2007 Jan 30. 115(4):442-9. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- London B, Michalec M, Mehdi H, Zhu X, Kerchner L, Sanyal S, et al. Mutation in glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like gene (GPD1-L) decreases cardiac Na+ current and causes inherited arrhythmias. Circulation. 2007 Nov 13. 116(20):2260-8. [Medline].

- Watanabe H, Koopmann TT, Le Scouarnec S, Yang T, Ingram CR, Schott JJ, et al. Sodium channel beta1 subunit mutations associated with Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease in humans. J Clin Invest. 2008 Jun. 118(6):2260-8. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Donohue D, Tehrani F, Jamehdor R, Lam C, Movahed MR. The prevalence of Brugada ECG in adult patients in a large university hospital in the western United States. Am Heart Hosp J. 2008 Winter. 6(1):48-50. [Medline].

- Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Nimmannit S, Chaowakul V, Bhuripanyo K, Likittanasombat K, et al. Arrhythmogenic marker for the sudden unexplained death syndrome in Thai men. Circulation. 1997 Oct 21. 96(8):2595-600. [Medline].

- Bezzina CR, Shimizu W, Yang P, Koopmann TT, Tanck MW, Miyamoto Y, et al. Common sodium channel promoter haplotype in asian subjects underlies variability in cardiac conduction. Circulation. 2006 Jan 24. 113(3):338-44. [Medline].

- [Guideline] Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, et al. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005 Feb 8. 111(5):659-70. [Medline].

- Wilde AA, Antzelevitch C, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for the Brugada syndrome: consensus report. Circulation. 2002 Nov 5. 106(19):2514-9. [Medline].

- Sangwatanaroj S, Prechawat S, Sunsaneewitayakul B, Sitthisook S, Tosukhowong P, Tungsanga K. New electrocardiographic leads and the procainamide test for the detection of the Brugada sign in sudden unexplained death syndrome survivors and their relatives. Eur Heart J. 2001 Dec. 22(24):2290-6. [Medline].

- Takagi M, Yokoyama Y, Aonuma K, Aihara N, Hiraoka M. Clinical characteristics and risk stratification in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with brugada syndrome: multicenter study in Japan. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007 Dec. 18(12):1244-51. [Medline].

- Junttila MJ, Brugada P, Hong K, Lizotte E, DE Zutter M, Sarkozy A, et al. Differences in 12-lead electrocardiogram between symptomatic and asymptomatic Brugada syndrome patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008 Apr. 19(4):380-3. [Medline].

- Sarkozy A, Chierchia GB, Paparella G, Boussy T, De Asmundis C, Roos M, et al. Inferior and lateral electrocardiographic repolarization abnormalities in Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Apr. 2(2):154-61. [Medline].

- Kamakura S, Ohe T, Nakazawa K, Aizawa Y, Shimizu A, Horie M, et al. Long-term prognosis of probands with Brugada-pattern ST-elevation in leads V1-V3. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Oct. 2(5):495-503. [Medline].

- Zorzi A, Migliore F, Marras E, Marinelli A, Baritussio A, Allocca G, et al. Should all individuals with a nondiagnostic Brugada-electrocardiogram undergo sodium-channel blocker test?. Heart Rhythm. 2012 Jun. 9(6):909-16. [Medline].

- Brugada P, Geelen P, Brugada R, Mont L, Brugada J. Prognostic value of electrophysiologic investigations in Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001 Sep. 12(9):1004-7. [Medline].

- Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, Pappone C, Della Bella P, Giordano U, et al. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation. 2002 Mar 19. 105(11):1342-7. [Medline].

- Gehi AK, Duong TD, Metz LD, Gomes JA, Mehta D. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006 Jun. 17(6):577-83. [Medline].

- Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, Meregalli PG, Gaita F, Tan HL, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010 Feb 9. 121(5):635-43. [Medline].

- Priori SG, Gasparini M, Napolitano C, et al. Risk Stratification in Brugada Syndrome Results of the PRELUDE (PRogrammed ELectrical stimUlation preDictive valuE) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Jan 3. 59(1):37-45. [Medline].

- Raju H, Papadakis M, Govindan M, et al. Low prevalence of risk markers in cases of sudden death due to brugada syndrome relevance to risk stratification in brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Jun 7. 57(23):2340-5. [Medline].

- Pelliccia A, Fagard R, Bjørnstad HH, Anastassakis A, Arbustini E, Assanelli D, et al. Recommendations for competitive sports participation in athletes with cardiovascular disease: a consensus document from the Study Group of Sports Cardiology of the Working Group of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology and the Working Group of Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005 Jul. 26(14):1422-45. [Medline].

- Antzelevitch C. The Brugada syndrome: ionic basis and arrhythmia mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001 Feb. 12(2):268-72. [Medline].

- Márquez MF, Salica G, Hermosillo AG, Pastelín G, Gómez-Flores J, Nava S, et al. Ionic basis of pharmacological therapy in Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007 Feb. 18(2):234-40. [Medline].

- Márquez MF, Salica G, Hermosillo AG, Pastelín G, Cárdenas M. Drug therapy in Brugada syndrome. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2005 Oct. 5(5):409-17. [Medline].

- Yang F, Hanon S, Lam P, Schweitzer P. Quinidine revisited. Am J Med. 2009 Apr. 122(4):317-21. [Medline].

- Postema PG, Wolpert C, Amin AS, Probst V, Borggrefe M, Roden DM, et al. Drugs and Brugada syndrome patients: review of the literature, recommendations, and an up-to-date website (www.brugadadrugs.org). Heart Rhythm. 2009 Sep. 6(9):1335-41. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Takagi M, Aonuma K, Sekiguchi Y, Yokoyama Y, Aihara N, Hiraoka M. The prognostic value of early repolarization (J wave) and ST-segment morphology after J wave in Brugada syndrome: Multicenter study in Japan. Heart Rhythm. 2012 Dec 27. [Medline].

Schematics show the 3 types of action potentials in the right ventricle: endocardial (End), mid myocardial (M), and epicardial (Epi). A, Normal situation on V2 ECG generated by transmural voltage gradients during the depolarization and repolarization phases of the action potential. B-E, Different alterations of the epicardial action potential that produce the ECG changes observed in patients with Brugada syndrome. Adapted from Antzelevitch, 2005.

Three types of ST-segment elevation in Brugada syndrome, as shown in the precordial leads on ECG in the same patient at different times. Left panel shows a type 1 ECG pattern with pronounced elevation of the J point (arrow), a coved-type ST segment, and an inverted T wave in V1 and V2. The middle panel illustrates a type 2 pattern with a saddleback ST-segment elevated by >1 mm. The right panel shows a type 3 pattern in which the ST segment is elevated < 1 mm. According to a consensus report (Antzelevitch, 2005), the type 1 ECG pattern is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome. Modified from Wilde, 2002. Image courtesy of Richard Nunez, MD, and EMedHome.com (http://www.emedhome.com/).

- Table. ECG Patterns in Brugada Syndrome

Table. ECG Patterns in Brugada Syndrome

| Characteristic | Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 |

| J wave amplitude | ≥2 mm | ≥2 mm | ≥2 mm |

| T wave | Negative | Positive or biphasic | Positive |

| ST-T configuration | Cover-type | Saddleback | Saddleback |

| ST segment, terminal portion | Gradually descending | Elevated by ≥1 mm | Elevated by < 1 mm |

SHARE